HABITAT

Managing Great (and Unrealistic) Expectations

Paula Chin in Board Operations on May 5, 2016

Cooperatives and condominiums that are self-managed are used to doing things their way – board members are hands-on, available to each other practically 24/7, and personally invested in every aspect of their properties. When self-managed buildings switch to professional management, boards often expect the moon when it comes to the services and time they’ll receive. In those cases, managing agents have to temper those great (and sometimes unrealistic) expectations and get everyone on the same page for a smooth relationship.

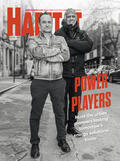

“Self-managed buildings are the toughest start-ups because they’ve been doing everything in-house,” says Mark Levine, principal at Excel Bradshaw Management Group (EBMG), which oversees some 60 co-op, condo and residential buildings in New York City and Long Island. Even with the best-laid management contracts, Levine says, “[board people] look at things from a different perspective than management firms, which can cause problems.”

The most common one, he says, is the frequency of board meetings. A typical yearly contract specifies a single monthly meeting, but boards sometimes reverse course and insist on more.

“I had one building that wanted to meet six times in the first six weeks,” he says. “I had to sit them down and explain that we had to stick to the contract or we would increase their fees – which of course no board wants – and they backed down.”

It all boils down to trust, in the opinion of Steve Greenbaum, director of management at Mark Greenberg Real Estate. “The hardest part is for self-managed boards to let go of day-to-day, full involvement,” he says. “They need to understand that we’re professionals with contacts with other professionals – engineers, architects, contractors. You need to build trust with any client – but especially with boards that were self-managed.”

Another bone of contention is how much time the managing agent spends on site. “Between visiting buildings, travel time, doing walk-throughs, physical inspections and dealing with things like roofs and boilers, even our smallest properties can take up at least ten hours a week of an agent’s time,” says Levine. With smaller buildings that don’t have superintendents or a full-time contact person, the agent becomes the de facto super and has to put in even more hours. Managing larger buildings, which also involves accountants and lawyers, can take up to fifty percent of a property manager’s time, Levine adds. “We can’t stretch our resources too thin,” he says. “Boards have to understand that we are offering a package of services, not unlimited hours.”

Sometimes feathers have to be smoothed over financials. EBMG offers clients complete online access to monthly financial reports and gives board treasurers read-only access to operating fund bank accounts if they request it. “But boards are still afraid of losing control,” says Levine, adding that it can be hard to get them to hand over documents like stock leases, deeds and payroll tax information. While management firms have to set the tone early that they will oversee day-to-day finances, Levine says, “we also have to assure them that at the end of the day, they’re still the boss.”

When problems can’t be ironed out, Levine says he’s had to give notice to the board and cancel the contract. Fortunately, that’s rare. “Most boards are reasonable and understand that time equals money,” he says. “When a management firm feels it’s not getting compensation for what it’s putting in, that won’t work for anybody.”