The Power of Unconventional Thinking

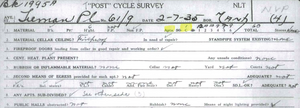

I-Card to the Rescue – this handwritten card saved a co-op big money (picture courtesy of Veritas Property Management)

Oct. 4, 2016 — Good things happen when boards and their managers avoid the easy route.

In April 2015, a Con Edison worker smelled gas while reading the meters at 69 Tiemann Place, a six-floor, 62-unit cooperative in Morningside Heights, near Columbia University in Manhattan.

“They shut down all of the cooking gas lines,” says Carl Borenstein, president of Veritas Property Management and manager of the 90-year-old building. “We had a plumber go through the system and do extensive repairs on the risers and branch lines,” he says. “We were all set for him to conduct a pressure test for a New York City Department of Buildings [DOB] inspection so Con Ed could turn the gas back on.”

But Borenstein got more bad news. The building would not pass an inspection for the super’s basement apartment or the boiler room because the DOB had no records of their legal existence. The dwelling did not have a Certificate of Occupancy (buildings built before 1938 were not required to have them), so Borenstein could not use one to prove otherwise. The DOB did have records of inspections and permits issued for the apartments, which established their existence, but none for the spaces below ground level.

“The DOB’s solution was for us to hire an engineer, submit construction drawings, and then file and pull electrical and plumbing permits just to prove the apartment and boiler room existed and were up to code, which would have taken months,” Borenstein says. “It was crazy.”

That’s when the manager had his “a-ha” moment. Several years ago, he had overseen the creation of a super’s apartment in the basement of another pre-1938 building without a C of O. “I needed to know if there had ever been a cellar apartment, and an engineer told me to pull the I-Card,” he recalls.

He was referring to the handwritten, index-sized cards from the early 1900s that documented, apartment by apartment, what structural “improvements” were required in multiple-dwelling buildings by the city’s earliest code inspectors. More than a million I-Cards have been digitized and are available to download for free at the city’s Housing Preservation and Development department’s website – an invaluable source of historical information for older buildings.

It took Borenstein just minutes to find the I-Card, which simply read, “Tiemann 69, cellar occupancy certificate #1952,” thereby verifying the existence of the super’s apartment. Borenstein had to dig a little harder for data on the boiler room, examining nyc.gov/buildings, where he found an “Actions by Locations” document with two entries, from 1939 and 1971, referencing oil burner applications.

“With those records, the city had to acknowledge that the apartment and boiler room existed,” Borenstein says. “I hounded the [DOB] commissioner for a whole week by e-mail and phone and made my case. Finally, he said, ‘You’re right,’ and told me to have the plumber refile the permit application to have all the gas lines turned back on.”

The property passed DOB and Con Ed inspections, allowing residents to go back to cooking with gas. The repairs on the aging gas lines took more than six months and cost $100,000, but, without Borenstein’s diligence, the co-op’s reserve fund would have taken a far bigger hit.

“I’d say we saved at least $20,000 by not hiring an engineer and applying for all those permits and inspections,” he says. “Instead of taking the path of least resistance, managers should look for alternative solutions. And having a good memory doesn’t hurt.”